Where are we at? Divergent and convergent processes

31 Mar

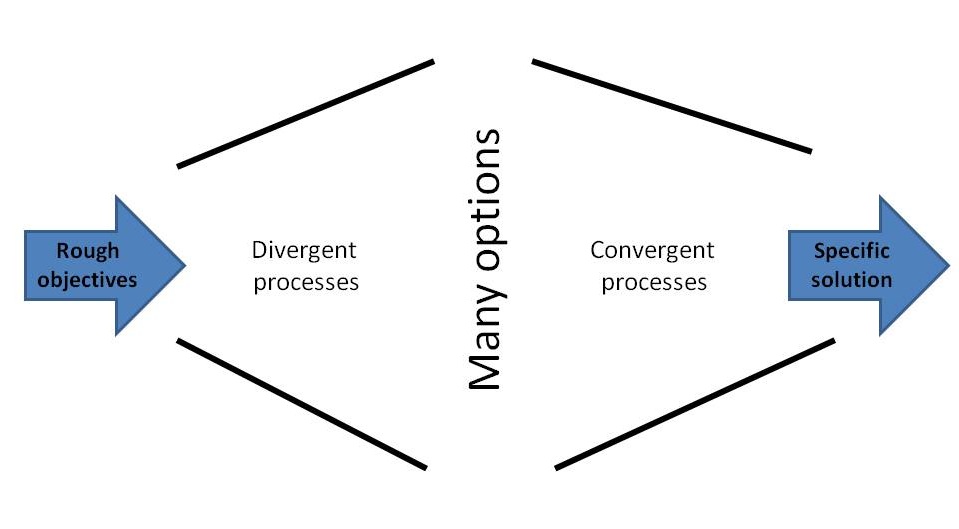

One of the key skills of a facilitator or a manager working with a group is to make the people understand what they are doing and why they are doing it – in other words – to make them feel comfortable about the process even though it might not immediately appear like the group is moving towards the intended outcome. One can apply this to his/her life as well to better understand where he/she is right now. While we can group these processes along many dimensions, the one I have found most useful divides processes into divergent and convergent ones.

The whole idea is that first we go wide, we diverge into many options, and then we go narrow again, we converge towards a solution. To illustrate this on a simple example, we can look at a process of trying to achieve a certain aim. Such process usually goes through several stages. A very basic divide would be:

1. We have a rough idea of what we want to achieve

2. We come up with many options of how we can achieve it

3. We select the best ones by applying various filters to all the options we came up with before

4. We execute those options

If we were to draw what is happening, it would look something like this:

Divergent processes

Firstly we diverge – we are creative, we brainstorm and generate as many alternatives as possible. This is very important because even if we would have very good criteria for choosing the best alternatives afterwards, we can end up with a bad outcome if we did not have any good alternatives to start with.

The problem is however that some people do not feel comfortable with this part of the process. After some time, they can either feel like they are losing time because they think sufficient number of alternatives has already been generated and they want to move towards choosing the best one or they feel uneasy and stressed about the sheer number of options, thinking that it might be impossible to ever come up with a simple solution. This is where the facilitator needs to step in and make sure that everybody understands that we are exactly where we should be at, in the divergent phase, and that we will converge in order to come up with a solution a bit later on. This makes people more comfortable with the process and allows them to focus on the problem more and to ultimately come up with a better outcome. Which is where the convergent phase comes in.

Convergent processes

The task is to narrow down the number of option to only a few best ones in the convergent phase. There are multiple ways of doing so such as applying certain filters (having cut-off points) or if they are mutually exclusive comparing trade-offs between the options .

It is worth keeping in mind that these processes can often be found within each other as well. For example when starting with only a basic idea of what we want to achieve, we might diverge in terms of our objectives only to converge to the most important ones later on and to subsequently start the whole process again with diverging into possible ways of achieving those.

I have used this concept many times during discussions with teams I lead to make sure we consider all relevant options and choose the best one. I have also been thinking about my life over the last couple years in this way. I have been travelling to many countries, trying various things and meeting lot of people in order to experience what all is out there in the world and to see what I really want to care about in the future.

So next time you feel a bit lost or feel like your chosen alternatives are not really that good, think about what part of the process you are in and decide if you should stay there a bit longer or if you should go one step forward or backward.

Recent Comments