Ideas from Stelios, the founder of Easyjet

22 Dec

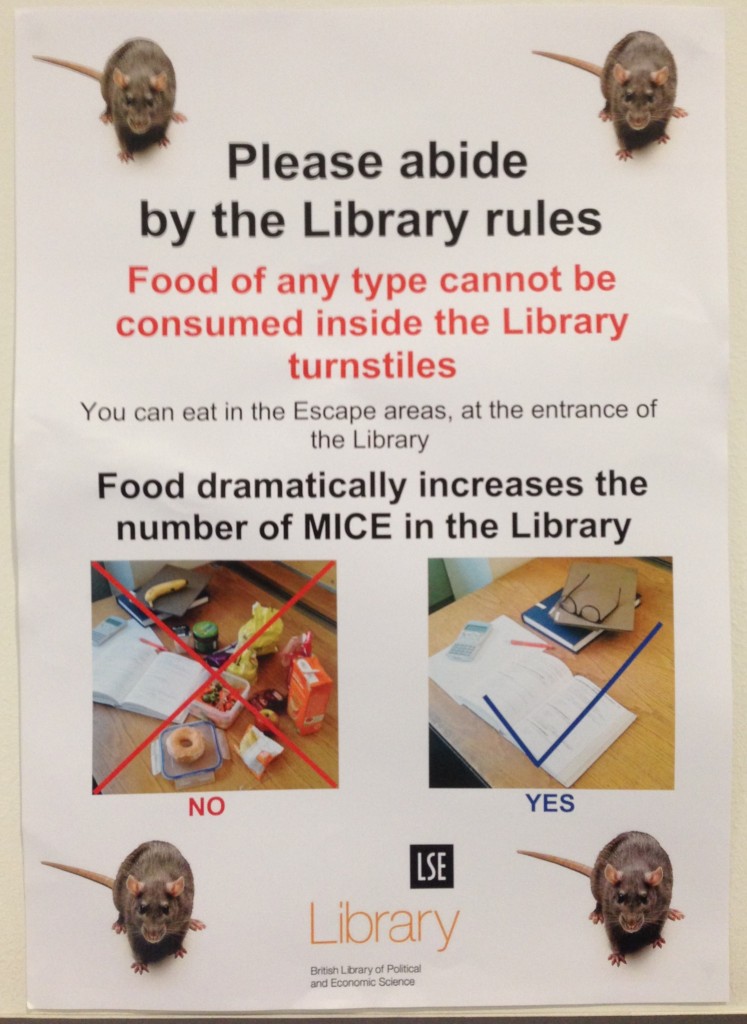

Another interesting person who recently spoke at the LSE was Stelios, the founder of Easyjet (and an LSE graduate). Here are some of the notes I took during his speech.

They revolve, albeit perhaps unintentionally, around the concept of Antifragility as developed by Prof. Thaleb and as outlined in my previous post. The world we live in is inherently volatile and unpredictable and therefore we need to structure our businesses in a way which would allow them to withstand this volatility.

Stelios does not believe in research, he prefers to learn by trial and error. Invest a (relatively) small sum, see how it goes and learn from it. Closely related to this is his second piece of advice – do not bet your farm. Learning by doing is all good but do not make a bet you cannot afford to loose.

Antifragility pertains also to his choice of industries to get into – the best markets are those benefiting from volatility. If the economy slows down, people start trading down and will fly Easyjet as opposed to legacy carries. If the market goes up, more people will be able to afford to travel and Easyjet will benefit as well. He was in a shipping business before which is very commoditised and when the market went down, everybody suffered.

The founder of Living Spaces, a room letting agency in London, spoke recently about a similar idea. It is best to focus either on the bottom segment of the market because if your product is relevant, the worst thing that can happen is that people will trade down, or on the other hand on the top segment where margins are fatter and better insulated from day to day volatility.

Finally, Stelios said that hard work breeds luck, a bit of cliche but a true one and that a good age to start a business is 28. By that time, one would have completed his/her studies, have worked for a couple of years and therefore would have identified what he/she is passionate about and are his/her strengths to build on.

Recent Comments