Context matters

24 Mar

I have been coming across the word context a lot lately. So much so, that it really forced me to think about it and to appreciate how vital it is to our ability to make good decisions as well as to understand decisions of others and the world around us as such. Is £1000 a lot of money? When your friend was angry some time ago, was she being unreasonable? Is 15 degrees a warm weather?

Well, we cannot answer any of those questions without knowing their context. Extra £1000 is a lot to a student living off couple hundred pounds a month but not to a company for which if might represent only a 0.1% increase on profits of one million. Your friend might have been unreasonable if the cause of her anger was having to work overtime on a one off basis but not if her boss shouted on her for no apparent reason. 15 degrees is pretty cold in summer but unusually hot in winter. This might all seem obvious but I would bet we don’t always take the time to understand the context before making or perhaps even more importantly, interpreting one’s decision.

Making a decision…

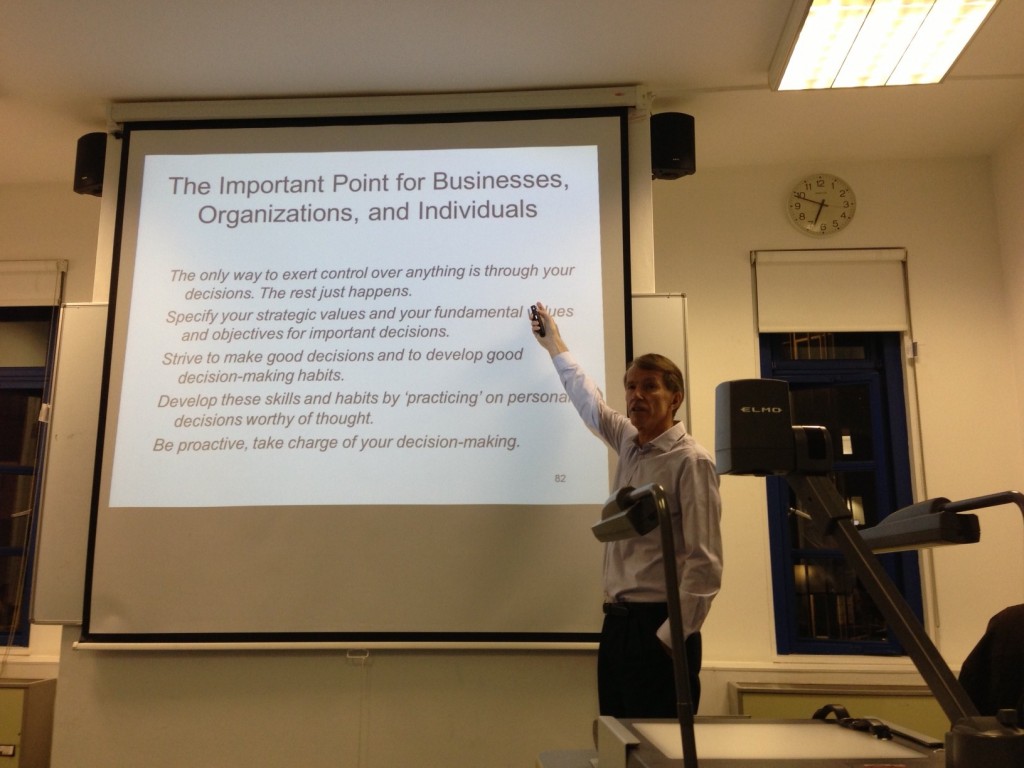

When making a decision, we need to realise what are the options we have realistically have, what consequences would they have, what is the likelihood of them working out and how would they be perceived – we need to know the context of the problem. If we come up with a model solution but we cannot implement it because of a specific organizational constraint, it’s a useless one. In a similar fashion, if we do not understand how the final decision maker will perceive our recommendation and if we would not be able to secure her buy-in, even the ‘best’ solution in the world would be useless in that context.

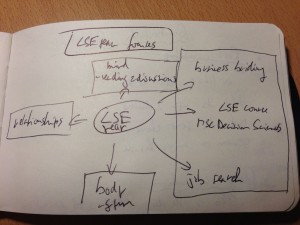

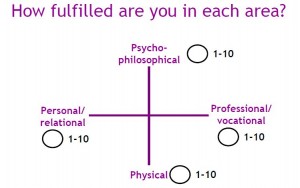

Organizational models (see for example my previous post here) or personality models, heuristics and preferences (e.g. if the final decision maker is risk averse, if she prefers quantitative or qualitative analysis, what are her key concerns etc.) are usually good starting points for gaining deeper understanding of our context.

…& interpreting a decision

Being aware of the context becomes even more crucial when we are interpreting someone else’s decision. What is an overreaction in some situations is an appropriate response in other situations and vice versa. Big risks can go unchecked and relationships built over a long time can go sour if we wrongly evaluate somebody’s decision. This can be because we were too lazy to dig deeper and understand the context in which that decision was made before we start judging it or because we misunderstood what message the other person was really trying to put across.

So remember, although it might sound obvious, context matters and it often matters more than you think!

Recent Comments